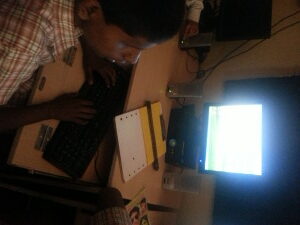

While teaching street kids in India how to pronounce English words, I realized something about vowels.

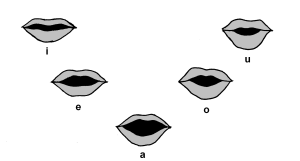

Vowels are snotty little bastards. In the world of letters, they are conceited, arrogant, and exclusive. They are shrewd at business and have a monopoly on the creation of most English words. Vowels have made themselves indispensable, and they use it to their every advantage. Like true elitists, they have a powerful lobby in the alphabet community. Vowels have convinced national TV game shows that there are only five of them. So when you need one, you have to buy their services. Not like the other 21 letters that end up paying you each time they are selected.

“It’s life,” they say. The wheel of misfortune.

But then there’s the letter “y,” who I have come to respect a great deal while volunteering here in India.

“Y” just smiles and serves. Each day, “y” wakes up in the morning, goes to work, and then walks back home. And it’s a long haul back to 25th Street, the second to last house at the end. “Y” lives in an area where there aren’t many jobs. His neighbors “X” and “Z” can’t find much work and they’re usually living hand-to-mouth. “Y” isn’t popular like A-B-or-C. He doesn’t brave new style like “S.” He isn’t unique in sound, either. His cousin “Why” has the same name as him, but — like the vowels — he also belongs to a snooty 5-member-only country-club (they call themselves “The 5W’s”).

But there’s something about “y” that I love. He refuses to be categorized. He refuses to be judged. “Y” says “Yes” to everything. Can you be a consonant? Yes! Can you fill in for a vowel? You got it! His mission is more than his ambition. He doesn’t fuss about what he is or what he isn’t. He doesn’t come up with excuses or ponder over what ‘could have been’ or what ‘should be.’ Instead, “Y” is a problem solver and team player. He begins words, ends words, and keeps words together, even those that can’t afford to buy their own vowels.

Just like letters, there are all sorts of people. Some are elite, many are not. Some are popular, others often overlooked.

But when it comes to happiness, there are only two types of people: those who complain “why” and those who become “y.”

Those who complain “why” are never satisfied. No matter how much we have, we always want more. When we don’t get more, we complain why not? When misfortune (no matter how slight) falls upon us, we complain why me? Even though we love having more, we constantly make excuses for why we cannot do more.

Then there is the second type: those people, who instead of complaining why, they just choose to become “y.” And I have encountered several of them during my travels here in Gujarat. Human beings who may not be part of the upper-caste vowels or the more popular-sounding consonants, but who still smile and serve each day to the end. Instead of making excuses for what they don’t have, they find uses for what they do have, and they refuse to be shoved into some shameful corner of the Earth just to do nothing. These “y’s” don’t feel sorry for themselves; they feel sorry that they don’t do more.

For example, there is Ramesh-bhai, a man who has been categorized as an “untouchable.” He lives in Ramapir No Tekro, the largest slum in Gujarat. He’s a “y.”

At a young age, Ramesh-bhai was born with polio in both his legs. A cripple who cannot walk, he was thought a burden to his family. He had every reason to ask why me? Instead, he found a purpose greater than himself. So every day, he wakes up, he forgets that he has polio in both legs, he crawls on his hands, he climbs onto a hand bike, and he pedals with one arm, in order to deliver tiffins of food to the elderly. He does this each day, twice a day, back and forth. Born a burden to two parents, he is a dutiful son to fifty more. He is to me a modern day Shravan. Why is it, I wonder, that

the heroic actions are performed by such as are oppressed by the meanness of their lives? As in thickest darkness the stars shine brightest.

THOREAU, Journal, 1842

Few of us can ever climb to reach Ramesh bhai‘s height in giving. Maybe he really is untouchable, I think to myself. Angelou tells us that everything in the universe has a rhythm, everything dances. Ramesh-bhai too, on his pedal bike.

Then, there’s also the blind school, located in Gandhinagar, the capital of Gujarat. Lots of “y’s” here, too.

The school serves blind children here who have never seen their own faces. Some kids have, but never again, because their sight was snatched from them by disease or gouging by their own parents. Every right to quit and ask why me? Instead, they abandon all misconceptions of their status and see only with their hearts. They make textiles, read and write through a punch machine, and access computers through sound. They open Word documents and type faster than most secretaries I know. One boy is asked, “It must be hard for you to be blind.” His reply? “It would be if I had no vision.”

And finally, there’s Jyoti-bhen, a poor widow who lives outside a narrow slum that I delivered food to. She is also a “y.”

One morning, I stopped the rickshaw near her home to deliver meals to some school kids who lived behind her. Jyoti-bhen sees us and begins to dance. I don’t know why she is dancing for us, and as I look into her small room/home, she has not much to call her own. Still, like a capital “Y,” both her arms branch out in opposite directions and she dances with her soul. Happiness can not be rationalized here. Where you expect to find suffering, misery takes a swig of hemlock. Jyoti-bhen is categorized an “untouchable” but we embrace her anyways. From the main road, wary eyes stop to watch us and judge. A Sufi proverb whispers in my ear. To those who cannot hear the music, the dancers look crazy.

Illiterate, then widowed, now ostracized, why does Jyoti-bhen still smile and dance?

Because rhythm has no vowels.

That is “y.”

—-

POST-SCRIPT: For those interested in learning more about the NGO I worked at, I would encourage you to visit Manav Sadhna. If you are logged into Facebook, I have also made available publicly an album of photographs of my time there.

Through these 5 parts (the concepts of space, jugaad, time, relationships, and happiness), the lessons I take back are my own.

But I can’t end this piece without a few words on untouchability, because we should not romanticize poverty. Not everyone is a “Y.” Millions are destitute and there is nothing romantic about it. As beautiful and rich of a civilization as India’s, she too has a dark underbelly. I have seen but a glimpse. Untouchables are regarded as the pollution of everyday life: the outcastes, the diseased, the deformed, the damned. They are from all religions and languages, each age and state and sect, a quilt of patchwork of various people sewn together from every imaginable distinction except one: that each and every one of them has been randomly stitched by the same inhumanity as the next. Because we don’t accept them into our world, 200 million of them are banished from the sight of most human beings into corners of the Earth so depraved that you can imagine no hell worse living.

There is no justification for this. But rather than blaming governments and finger-pointing over whose turn it is next to babysit our own shame, I was inspired by those groups who woke up everyday and decided to do something about it. Yes, it is easy for me to say. I’m an outsider to my own place of birth. Still, two eyes and ears can go a long way and a blurry line began to divide what I thought was heaven and hell. The slums, it turned out, are not some polluted, filthy waste land. “Houses” here are homes like anywhere. And as we drank from their cups and ate from their plates, as we sat on their beds and picked up their kids, got closer to their comfort zone and ventured farther from our own, a very strange self-awareness set in fast. These people – who fed us with their warmth and saturated us with their love, who had but a few shirts and dollars to their name – reminded us that in our world “some people are so poor, all they have is money.”