For as few words as Hindi has devoted to the concept of Time (Lesson 3), when it comes to family relationships, it’s the exact opposite: there are no shortage of words.

And that’s because relationships in India matter. They matter a lot.

In English you say, “I’m going to my aunt’s house.” Which aunt? Your dad’s sister? Your mom’s sister? Your dad’s brother’s wife? Your mom’s brother’s wife? Only you know where you’re going.

But in Hindi (and most Indian languages), everyone knows where you’re going because there’s a different word for your dad’s sister (bua) and a different word for your mom’s sister (masi). There’s a different word for your dad’s brother (chacha) and a separate word for your mom’s brother (mama). There’s a different word for your dad’s mother (dadi)and a separate word for your mom’s mother (nani). A separate word for your dad’s dad (dada), and a separate word for your mom’s dad (nana).

Why so many names? Because when it comes to love, no one here gets sloppy seconds. The irony is that even though Indians love to share spaces with total strangers (Lesson 1), when it comes to family, Indians hate sharing attention.

People here get awfully sensitive and possessive of their relationships. Just as you study “Newton’s 3 Laws of Motion” to understand physics, to understand Indian relationships, I present to you “Kundani’s 3 Rules of Relations.”

This concept was described above. In India, there is no guessing when it comes to a relationship. A separate title for your dad’s brother and a separate title for your mom’s brother ensures that both men will sleep happy at night knowing that they are not sharing their “uncle” status with the other side of your family. One is your chacha, the other your mama. Sometimes, peace comes through division.

Be forewarned though. There are corollaries to Rule #1.

That’s right. Even these non-blood-related people get their own names! These are the people your family members decide to marry and once they do, get ready, because your life gets a tad more confusing.

Your sister s husband becomes your jija, your mom’s sister’s husband becomes your masaad, which is different from your dad’s sister’s husband, who becomes your phupha. Your brother gets married and his wife becomes your bhabhi, your mom’s brother’s wife becomes your mami, which is different from your dad’s brother’s wife, who becomes your chachi.

If Rule #1 applies to the spouses of your family members, then it applies just as equally to the family members of your spouse.

Lets’ say one inexplicable day, you decide to get married. Suddenly, your spouse’s mom becomes your saas, your spouse’s father is your sasur. Your husband’s sister is called your nanad but your wife’s sister is called your sali. Your wife’s brother is called your sala, but your husband’s brother is called your devar, unless, of course, he is your husband’s older brother, in which case he is your jeth (we will cover this in Rule #2).

Yep. Kids have rights, too. When you have children, or your siblings have children, or your kids have children, Rule #1 grants each of them a separate and unique title so they too can feel special.

Your son is your beta, your daughter is your beti, your son’s wife will be your bhau, and your daughter’s husband your damaad. Your son’s daughter becomes your pothi, but your daughter’s daughter is called your naatin. Your son’s son is your potha, but your daughter’s son is your naati. Your sister’s son is your bhaanja but your brother’s son is your bhatija. The daughter of your brother is your bhatiji but the daughter of your sister is your bhaanji.

But, of course, this is India, and we’ve only reached intermission. Because when they were drafting Rule #1, someone in all of this stopped and said, “Oh, but wait! This isn’t good enough! Because now the spouses of your spouse’s siblings will feel bad because they don’t have a name.”

And so it continues. Your wife’s brother’s wife becomes your salhaj while your wife’s sister’s husband becomes your saadu. Your husband’s sister’s husband is your nandoii while your husband’s brother’s wife is your devrani unless, of course, she is married to your husband’s older brother, in which case, she is your jethani.

Now you wonder why divorce is rare in India? By the time it takes you to memorize Rule #1 and its corollaries, you will likely already be cremated. “I spent the past 25 years memorizing all these names for nothing? Hell no, we’re not divorcing!”

Seriously, when you take a step back, and really ponder Rule #1, it’s not that older Indian parents are really against gay marriage. They’re probably just worried about what to call one other after the marriage. My son’s husband is my what? What’s the word for my sister’s wife? God forbid we break Rule #1 and someone in India doesn’t have a unique name! “Gay marriage shall be suspended until we can figure out more names for each other.”

Just when you get to the point of finally memorizing all of these names and relations, and just when you start to think “Wow, this is such a warm and fuzzy feeling, everyone here feels included,” get ready to throw it all out the window. Because in the card deck of Indian relationships, age is the joker, the wild card, and the ace of spades all in one. If you have this card, you always play it, because age here trumps everything.

Rule #1 flows upstream because title here flows upwards. When speaking to someone older, you referto them with respect and by their proper title, never by their name. And if you do use their name, you always add on their title. It’s a bumper sticker that everyone should see and that never peels off.

But when speaking to someone younger than you, well…..you can basically refer to them however you damn well feel.

So whenever there is any gap in age, no matter how slight, Rule #2 is in effect. If you are the older twin brother by even two minutes, you forever are bhaiya and your younger twin brother, who is taller than you and stronger than you, is whatever you decide to call him. His name changes like the weather and he will evolve through many pet names of your choosing, not the least of which will be chotu, the infamous Indian name branded on every younger sibling at some point in their earthly existence. Not having a title in India is not cool, but neither is being called chotu. Though it innocently means “small one” at a young age, by the age of 30, it almost means “dweeb.” Chotu will never get to pull the bhaiya card until he finds another chotu in the form of a younger sibling or cousin. (In India, cousins are as good as siblings).

A few helpful principles to keep in mind when dealing with people’s ages here.

What happens when you are older than your uncle? (In a land where grandparents were married at age 12, it’s more common than you think).

Or what happens when you don’t know who is older and you don’t want to call them by their name but you also don’t want to surrender and call them by their title?

This is when “The Ji Principle” comes in handy. Add a ji to the end of their name, and you instantly give them mini-respect. It may not hold you over forever, and at some point you might have to revisit the issue with them more formally, but it’s an instant fix that will buy you some time.

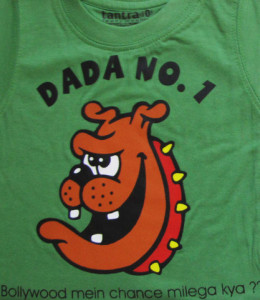

There are few people higher in Indian relations than a dada. And I’m not talking about your paternal grandfather. I’m speaking about the guy who’s not even related to you or your family, but when he comes in the room, every member of the family stands up and starts calling him dada. If you see this happening, this is an extremely reliable indicator that this guy is a godfather of sorts and you should get ready to do the Indian equivalent of kissing his hand; get ready to touch his feet. Always tread carefully near a dada. They didn’t get there by accident.

In the world of Indian family relations, there are two people who won out big time. They aren’t most people’s first guess, though.

The older brother (of a younger brother) and his wife are what I call the “Big Dogs” in the Indian name-dropping world.

Check it out.

When a wife refers to the husband’s younger brother, she calls him devar. But when she refers to the husband’s older brother, she calls him by a different name: jeth. And jeth’s wife also gets a special name, too, jethani, as opposed to the husband’s younger brother’s wife who is called devrani.

(This separate term for a husband’s older brother does not happen in any other similar relationship. When a husband refers to his wife’s younger or older sister, the sister is his sali. When a wife refers to her husband’s younger or older sister, the term is nanad. When a husband refers to his wife’s younger or older brother, the brother is the husband’s sala.)

But the Big Dogs aren’t just special because the sister-in-law calls them by a different name. Other people in the family also see them as Big Dogs and call them by special names, too.

For example, a kid will always call his mom’s brothers mama. He will always call his mom’s sisters masi. A dad’s sisters are always called bua. Their ages don’t determine their name. But when it comes to the father’s brothers, their names are again differentiated by age. A kid calls his father’s younger brother his chacha but to the Big Dog (the father’s older brother), he calls him tao. (Yes, spelled like the Vegas nightclub). Tao’s wife is tai because she is also a Big Dog.

These special names given to the husband’s older brother and his wife (jeth/jethani and tao/tai) is no small matter. To appreciate this, consider that a husband’s father and a wife’s father get the same name, sasur. The husband’s mother and wife’s mother also get the same name, too, saas. But a husband’s older brother gets his own name, and his wife too, unlike any other relationship.

This is called “The Big Dog Principle.”

(And by the way, because it probably has more to do with property inheritance, the Big Dog Principle is not gender discrimination as much as it is age discrimination. Chotu gets screwed here just as much again).

And can you blame us? With all these rules and corollaries and principles, with such an extended network of new family members and each with their own names, with over a billion people and still growing, how do you really know if someone you just met is your mom’s sisters’ son’s wife’s older brother? Because if he is, he is your deur ki bhaiiya, and you just blew it by calling him Sunilstraight to his face!

So Rule #3 is what all Indian people finally decided on one sensible day. We need a safety net, they thought. And, just like that, every older man can be called your “uncle” (ung-kal) and every older woman could be your “aunty” (ahn-ti). And it was one of the best ideas to ever evolve from this chaos. This is why when you meet a complete stranger in the Indian store, you just call her “Aunty,” because chances are, she probably is your aunty and, even if she’s not, she probably will be some time soon.

Still, this doesn’t solve all problems. Especially at family reunions.

A family reunion is one of the most confusing times for an Indian. Not just memorizing all the relations. But during a group conversation with other family members, people will be talking about the same family member but will be referring to them by a different name than you. (If you’re Indian, you know what I mean. If you’re not Indian, there is nothing quite like it).

Here’s an example. My bua is my father’s sister. But that’s how I refer to her. My cousin can be talking to me about my buabut would refer to her as masi (his mother’s sister). But when I hear him say masi, I think of my mother’s sister (instead of my father’s sister) and this can lead to some juicy gossip really fast.

Here’s a tongue twister. Consider that my bua is his masi and my phupha is his masaad. My mama is his mami but his mama is my daddy. My sali’s husband is my saadu but my wife calls him jija. My sala’s sister is my wife but she calls him bhaiiya. My tai’s devar is my father whose daughter I call didi, but my father’s brother is my chacha whose bhaiiya calls him chotu. My wife’s devrani is my bhabhi but my brother calls her biwi. My biwi’s devar is my brother whose bhatija calls me daddy.

Given all of this, it now makes complete sense to me why Indian parents are always in a rush to get their kids married and pushing them to have children.

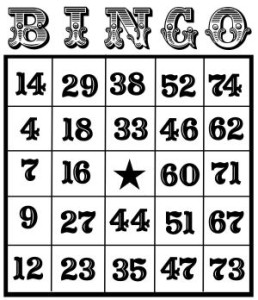

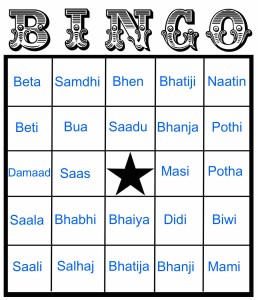

Think of Indian relationships like a Bingo game. In Bingo, the first one to get all of their numbers called wins.

Similarly, Indian parents have their own version of Bingo cards. I think it looks something like this.

A list of 24 relations that every Indian parent must have in their lifetime. Whoever gets all of them first, wins.

Does this conversation sound familiar?

“Come on, beti. Get married!”

“Why Dad? Why are you pushing me so much?”

“Because it’s time for you to just get married only.”

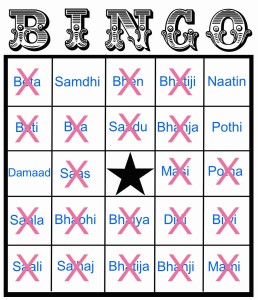

That’s not the reason why. Take a look at Daddy’s Bingo card.

The minute you get married, he gets to scratch off damaad (son-in-law) and samdhi (the relationship given to the two fathers of a married couple). And the second you have a daughter, he also gets to scratch off naatin (daughter’s daughter).

But is Daddy happy once you get married and after you have a daughter?

Nope. He goes to your brother who is already married and who already has 3 sons.

“Beta, I think you should have a daughter now.”

“Dad, why? I already have 3 sons, and your daughter just gave you a granddaughter.”

“Yes, I know but if you have a daughter, then my granddaughter will have another girl to play with. Please have a daughter beta.”

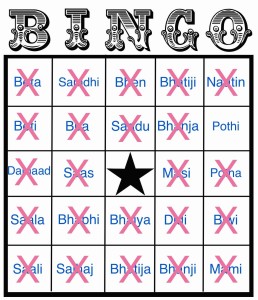

Why is Daddy pushing so hard? Check out what’s missing on his Bingo card now.

That’s right! One relationship away from winning! All Daddy has left is a pothi. A pothi (son’s daughter) is different from a naatin (daughter’s daughter), which Daddy already has. And both of those are different from a potha (son’s son), which Daddy already has 3 of. Just one pothi will win him the grand prize. (And what’s the grand prize if Daddy wins? A teerthayatra of course!)

When you understand that there are over a billion Indian people playing Indian Bingo, you then understand why there’s an Indian overpopulation crisis and why they keep trying to have more kids. It also explains why every aunty is trying to hook you up. (Even the aunties are trying to get in on some Bingo action).

All jokes aside, Indian relationships are a never-ending maze of names and faces and ages and small worlds. The ancients didn’t waste any unnecessary words to describe time (the fact that Hindi has one word for “tomorrow” and “yesterday” is telling). Instead, they placed great emphasis on living in the present and devoted more words to relationships, reminding us that each role in our lives is unique and different: a daughter to your mother, a daughter to your father, a sister to your brother, a sister to your sister, a wife to your husband, a daughter to your husband’s mother, a daughter to your husband’s father, a mother to your son, a mother to your daughter, an aunt to your brother’s kids, an aunt to your sister’s kids, an aunt to your husband’s brother’s kids, an aunt to your husband’s sister’s kids, a sister to your husband’s brother, a sister to your husband’s sister, a sister to your sister’s husband, a sister to your brother’s wife, a grandmother to your daughter’s sons, a grandmother to your daughter’s daughters, a grandmother to your son’s sons, a grandmother to your son’s daughters. To the ancients, each of these relationships was different. And because it was different, each had its own special name based not “-in-law” (e.g., sister-in-law) but “-in-love” (e.g., masi, which literally means ‘half-mother’ or ‘part-mother’).

It is easy for us to lose track of this these days where we too often cookie-cut our roles and copy/paste our actions just to get through our day. Our lives really are a lifetime of different roles.

In Hindi, there are 3 ways to say “you” – familiarly (tu), casually (tum), and formally (aap). When it comes to speaking to one’s parents or a boss or someone older than you or a teacher, or if you want to be polite, you refer to them using the aap form of “you.” When you are talking to an acquaintance, or someone your own age, or speaking to someone you are very familiar with, you refer to them in the tum form of “you.” But when it comes to speaking informally to someone, or to a close friend, or to command someone, or when you want to insult someone, you refer to them in the tu form of “you.”

To me, the most beautiful irony when it comes to Indian relationships is that despite all the formalities and all the titles we have for one another, and even though we have 3 different ways of addressing someone, when an individual – no matter how young or old – will address God, he/she will do so in the most informal way possible, referring to God in the tu form.

Because Indians are possessive of their relationships, God here belongs to everyone. And because many view God like a personal friend, belonging to you just as much as to anyone else, Indians will refer to God using the informal tu form. Many Hispanic-speaking nations do the same. It is one of the most humble tributes that Religion has ever paid to Language.

The women praying in the above picture are known as a maa-jis. This literally means “mothers” (see also ‘The Ji Principle’). In Ahmedabad, many of these women are alone, with no families, widowed or abandoned. Even though they weren’t our own mothers, by simply calling them maa-jis, we automatically transformed them from complete strangers into our actual mothers, and so the relationship transforms accordingly (“a rose by any other name” smells just as sweet). We sit with our new mothers, wash their feet, massage their heads, sing with them, give them shoes, and fill their bags with grain.

Words alone can create relationships in a heartbeat. And in India, all relationships matter here — even those created among strangers.

– – – – – – – – –

POST-SCRIPT: There are many Hindi words (and non-Hindi words) to describe relations, and sometimes multiple spellings and usages of same or similar words. I am by no means an expert in Hindi, or any other Indian languages, so if I got something wrong or you have more words to share, feel free to chime in.