Lesson 3: The truth about Indian Standard Time.

“I’m sorry to ask you this,” she said. “But something I do not understand. Why are Indian people always late? I have noticed this ever since I have been here. No one here comes on time. Even the musical is now starting late, why?”

My friend and co-volunteer “Mary France of France” (as I called her) asked me this loaded question as we sat waiting for the show to start. It was my last night in Ahmedabad and a group of the volunteers here decided to go watch a show at a nearby outdoor theater. The show was obviously behind schedule and I – but a mere spectator – was expected to now explain the mystery of the great Indian time machine.

I answered with a question of my own.

“Mary France of France, how do you say ‘yesterday’ in French?”

“Hier,” she replied.

“And how do you say ‘tomorrow’ in French?”

“Demain,” she replied.

“OK. You have separate words for each, yes?”

“Of course!”

“OK. Now, how do you say ‘yesterday’ in Hindi?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she said.

“The word is ‘kal’. How do you say ‘tomorrow’ in Hindi?” I asked.

“I don’t know.”

“The word is also ‘kal.’”

She began to slowly process this.

“Really? The same word?! What?”

“I’m not joking,” I told her. “So for a culture that has the same word for ‘yesterday’ and ‘tomorrow,’ how do you expect us to ever be on time?” I asked.

Mary France of France couldn’t stop laughing. But it was true.

Time is a funny concept here in India.

On one hand, people here always act like they are rushing to get somewhere.

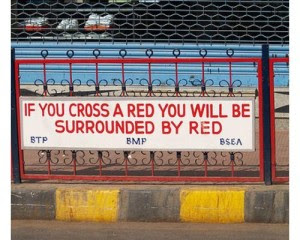

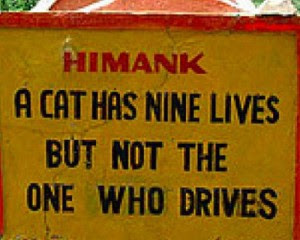

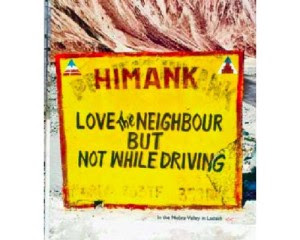

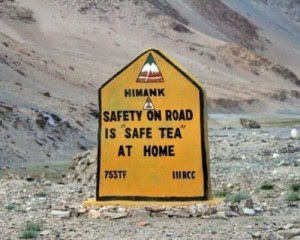

They constantly cut in front of you in line all the time. They honk their horns incessantly. They drive like mad to get to the next destination. They speed on the major highways at every chance they get. So much so that the road signs here have to come up with creative slogans to remind them to slow down.

On the other hand, despite this constant appearance of rushing everywhere, people here are always late. In fact, everything here is late. The trains are delayed, meetings are rescheduled, the flights are cancelled. At a party, late is not measured by what time youarrive but by what time others arrive. If you are two hours late, you might be on time. If you are three hours late, you might be early. Einstein didn’t have to look far past Indian weddings to confirm that time is a relative concept.

But time in India is even more complex than some universal equation. When Indians refer to time, they often speak in code. For example, saying you will meet someone “tomorrow” doesn’t really mean “tomorrow.”

“Keshav, I will see you tomorrow for lunch at your place.”

“Great, Ashok. See you tomorrow!”

Here, it just means “some time soon.”

For others, “tomorrow” has an entirely different meaning. My friend and co-volunteer Jose learned this first hand.

Jose went to buy a SIM card in Ahmedabad. The storeowner informed him that he did not have the SIM for that phone.

“When will you have the SIM?” Jose asked.

“Tomorrow,” the guy said.

So, of course, Jose went the next day.

“Do you have the SIM card?” Jose asks.

“No, don’t have.”

“I thought you said you would get it to today?”

(Silence)

“Sir. Yesterday you said to come today for SIM card.”

“No. Don’t have. See, look. Don’t have.”

“Okay. When will you have it?”

“Tomorrow.” (Head wobble)

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, sure.” (Smile; head wobble)

The next day:

“I’m here for the SIM card.”

“No, sir. No SIM card.”

“You told me 2 days ago you would have it!”

“Sir, we no sell SIM cards.” (Smile; head wobble)

Are you joking??!! Jose’s head was going to explode.

I tried to explain to Jose. “Here, the expression ‘tomorrow’ doesn’t always mean ‘tomorrow.’”

“So why the hell did he keep saying ‘tomorrow’?”

I tried to hold back my laughter and explain how the storeowner probably didn’t want to be rude, but I couldn’t stop laughing because it made no sense even as I explained it.

In India, putting something off into the future is just a nice way of saying never.

One day, as we were in a meeting with some locals, one man kept getting phone calls. Each time, he answered his phone and said, “Yes, I am just 10 minutes away.” Then, ten minutes later, another phone call. “Yes, I will be there in just 5 minutes,” he said. He stayed with us for over two hours and got a few more of these phone calls. Each time, more promises of arriving soon. After the meeting, I politely asked him, “Where are you going afterwards?”

“Nowhere,” he said. “I am here all day.” (And he was.)

Again, I politely asked him, “So why did you keep saying you are on your way?”

He smiled at me. “No, my friends are making a plan. It is easier to say I am coming than to explain why I don’t want to go.”

When one person stretches the truth, it’s called lying. When an entire country stretches the truth, it’s called Indian Standard Time (IST). IST refers to the geographic time zone carved out on a map for both India and Sri Lanka. But IST also refers to the well-known joke about how bad Indians are with time. Because time is malleable here, Indians themselves have renamed it Indian Stretchable Time. They’re almost half-proud of it.

“Yeah, yeah, come to my place by 9 p.m. IST, ok?” (Decoded: Call me at 9pm to see if we are still on).

But it’s not only this simple play on words that highlights how dysfunctional Indians are with time. It’s more that IST even exists in the first place. Think about it! Indians are so notoriously late that they were given their own freaking time zone! This means no other country wanted to share a time zone with Indians because they knew how late we always are!

Don’t believe me? I offer you Exhibit 1, this time zone map of the world.

Do you see India? If you look at the very bottom of the map, India is mainly under the (+5) column. If you follow the column up, and move north of India, there are other countries also in the +5 column. But they have a different time zone. A good part of Russia, for example, is in the +5 column, but guess what? Russia said “hell no” when asked if they wanted to join Indian Standard Time.

I’m pretty sure the phone call went something like this:

Russian president: “Hello?”

Indian prime minister: “Namaste, Mr. President.”

Russia: “Yes, namaste Prime Minister sahib. To what do the Russian people owe this pleasure?”

India: “Yes, actually we were looking at map. And we notice we are both-both in same longitudes.”

Russia: “What?”

India: “Yes, uh, Mr. President, you just do one thing.” (“Do one thing” is a popular Indian expression. It rarely means just one thing.)

Russia: “Okay.”

India: “You look at map, no?”

Russia: “Yes, I’m looking at the map.”

India: “Okay, now, you just do one thing. You look at the +5 column.”

Russia: “Yes, I’m looking.”

India: “You see that India and Russia, we are both same-same in +5 column, no?”

Russia: “Yes.”

India: “So this means we can be part of same time zone, no?”

(Silence)

India: “We think it will be benny-facial to both countries, no?”

Russia: “Yes, Mr. Prime Minister. I will get back to you on this. Maybe tomorrow, let’s say.” (Russia knew the lingo.)

I mean, think about it. Russia, the largest country in the world, has 9 different time zones ranging from the +3 column all the way to the +12 column. The only one time zone in that entire range it doesn’t use is the +5 (Indian Standard Time). You doubt me? Read here.

If that’s not insulting enough, check out Bhutan, Bangladesh, Maldives, and Nepal. I mean, these countries are literally sandwiched inside of India’s time zone. Indian Standard Time is on both sides of them. They got to be on IST, right?

India: “What do you mean you want your own time zone?”

Nepal: “We just think it would be best.”

India: “Is it because we’re always late?”

Nepal: “No! Don’t be silly. It’s just better this way.”

India: “But how would that even work? We are to the east and west of you. They’ll never give you your own time zone!”

Nepal: “Actually, we were able to convince Greenwich.”

And can you imagine that call?

Nepal: “Come on man, you can’t stick us with the Indians! Those guys don’t give a $h!t about time!”

Greenwich: “I know, but it’s really hard for us to justify why you can’t join theirs. I mean you’re sandwiched between India.”

Nepal: “Please, for the love of God, man! Do something! Just not Indian time!”

Greenwich: “OK, OK. Tell you what, we’ll switch you out for Sri Lanka.”

Nepal: “Oh, God, thank you! But what will our time difference be? An hour is way too much.”

Greenwich: “Yeah. That’s the problem. Hmmm. OK, tell you what. We’ll separate you from the Indians by 15 minutes. That’s the best we can do.”

Nepal: “We’ll take it!”

Greenwich: “We’re gonna have to find a creative way to explain this one.”

Think I’m joking? Look it up here. Nepal, sandwiched in the middle of India, has its own time zone separated from IST by 15 minutes! Seriously. 15 minutes! It’s one of the rare times on Earth where if you fly West to East (Kathmandu, Nepal to Manipur, India), you will actually go backwards in time!

That’s how bad Indian Standard Time is! Educated people felt it was better to just defy math and make human time travel possible rather than to inhumanely force people to share time with Indians!

As the joke goes here, the only thing on time in India is cricket. And that’s because the umpires aren’t Indian.

Time in India is the proverbial ‘elephant in the room.’ Everyone here for some reason seems to dodge it while talking. Even simple conversations I would have with people about plans.

Him: “So after lunch, why don’t we meet?”

Me: “Ok, so when exactly?”

Him: “Yes, after lunch.” (Head wobble; begins to walk away)

Me: “Yes, ok. But what time?”

Him: “Huh?!” (As if I cursed at him)

Me: “No, I’m saying what time do you want to meet?”

Him: “Time? Anytime. After lunch sometime.”

Since personal space in India doesn’t exist (see Lesson 1), Indians here aren’t very shy in asking questions of me.

“What do you do in America?”

“How much do you make?”

“How big is your house there?”

“How many floors does it have?”

“How much did it cost?”

“How many rupees is that?”

“Are you married?”

“What does she do?”

“How much does she make?”

“Was it a love marriage?”

“How many kids do you have?”

“Why don’t you have any kids?”

“What is your dad’s name?” (The most common question I was asked in the slums)

“What does your dad do?” (Second most common question asked in the slums)

“What did you eat on the plane ride here?” (Few people asked this)

But in the past two months here, the one question I never got asked is, “What time is it?” Out of all the questions asked, all the people I met, all the places I went, all the spaces I was in, not one single person ever asked me the time. As though that question would be invading my privacy.

Very quickly, you learn here that no one asks what time it is, because the time here is always now. India is faithfully married to the Present but, rest assured, is being seduced byTime constantly.

Allow me to expose her dirty laundry. The ancient Indians thought about Time a lot. Probably more than they should have been. If they wanted separate words for “yesterday” and “tomorrow,” they could have easily done so (there’s no lack of words or languages here). But the ancients decided that “yesterday” and “tomorrow” should be the same word, kal. And I would like to believe they were on to something. Stay with me here.

What is the Hindi word for “day before yesterday?” Parso.

What is the Hindi word for “day after tomorrow?” Parso.

What is the Hindi word for “day before day before yesterday?” Tarso.

What is the Hindi word for “day after day after tomorrow?” Tarso.

There is logic in this limbo, but you need to philosophize a bit. Whether you’re describing the past or the future in Hindi, the baseline is measured always from today. ‘Tomorrow’ and ‘yesterday’ are both separated by equal amounts of time from today, so they get the same word (kal). Just like how 48 hours from now and 48 hours ago are separated by equal amounts of time from the present, so they also get the same word (parso). Past and future are equally (in)significant concepts when compared to the present. The past is gone. The future has yet to arrive. So there is no reason to differentiate by name that which does not exist. What only exists is today and that is all that matters, so it gets a unique name. And the Hindi word for “today” (aaj) is very much linked to the Hindi word aaja, which means “come here.” Literally embracing the present. Pretty deep, huh?

Wait. The love affair goes deeper…

If you add a vowel sound to kal (yesterday/tomorrow), you get kaal, the Hindi word for Time. This makes sense (yesterday/tomorrow are both units of time). But then kaal is also the Hindi word for Death. And if you think about it, that also makes some sense (both Time and Death are constant and wait for no one, so they get the same word). And then of course – since Indians love math – why not throw in a little Transitive Property into the mix and make a logic problem out of it?

If Yesterday/tomorrow = Time.

And if Time = Death.

Then Yesterday/tomorrow = Death

And this makes sense too. Because “yesterday” is already gone, and “tomorrow” doesn’t yet exist, so as concepts they are both dead. What remains alive then is only “today.” Hence the phrase, “Live for Today.”

Just when you think you understand India’s marriage with the Present and love affair with Time, enter the rude temptress, Religion.

Many Indian religions believe in time as cyclical rather than linear. Not everything is meant for the Present because this may be just one life in many lives before and after, they think. Even gods and goddesses must die and then get reborn. To understand this, just understand the famous Ganpati Visarjan festival, where the elephant god Ganesha is worshipped and prayed to for 10 days and then his statue is immersed into the sea to disintegrate afterwards. He is momentarily gone, but with time, he will return. Because in India, nothing is forever, not even Death.

So there you have it. India’s eternal courtship with the Present and its kinky interludes with Time. A fiery yet faithful marriage built on the firm vow that there is only today and ‘not-today.’ Muslims here qualify their future with “Insha’Allah” (iA) and Christians with “deo volente” (DV). Time is an act of God that no one here presumes to plan.

You can see this love for the Present everyday in the streets of India. If a man gets sleepy in the middle of the afternoon, even though he is sitting on top of a ledge in the middle of a busy street in Mumbai, he will go to sleep right then and there. No questions asked. The time for sleep has come, and he simply surrenders to the moment. The great, eternal and indestructible ‘now.’

If two fruit-stall owners are fighting with one another, they will do so publicly. I watched one day from my window as they shouted and screamed and yelled and got into each other’s faces. One man even struck the other on top of his head. Twenty minutes later, they were peaceful and laughing, with no evidence of the minutes beforehand. Time had moved on and they moved with it.

I am by no means advocating that we should all quit our day jobs and take siestas in the middle of busy highways. Nor am I sanctioning street brawls with neighboring competitors. Neither is particularly safe. But what I am observing here are small acts of simplicity and spontaneity that are very organic and very genuine. They come and go without overthinking or hyper-stressing. People just living sincerely in the moment of things with very little attachment other than the here and now.

These moments of time come like a tide, and too many times we all go against it: checking our calendars before it arrives, clearing our schedules to see if we can ride it, reading reviews of who else has done it, and strategizing whether it will take us to where we think we need to be. Sometimes, we need to surf life just like we surf the web, where 3 clicks and 20 minutes later, we find ourselves somewhere far from where we had ever intended.

Christopher Lowman of New York City, a friend I met in the Leprosy Colony, did just that.

One day, after years of working in Los Angeles and New York, Chris just decided to ride the tide and throw his cell phone (read: handcuffs) into the proverbial ocean. For the past three years, he lived (among other places) with a community of lepers on the outskirts of Ahmedabad in a slum called the Leprosy Colony, or as we call it, the “Loving Community,” because of the unconditional love these men, women, and children will give to you when you take the time to enter their world.

These men and women are leprosy patients but know all about living in the present. Their bodies are permanently disfigured because of a simple infection that can easily be cured. But because leprosy in India carries a severe social stigma, even on the family level, these “lepers” (as they are called) were forced to leave their own homes (mostly in South India) and relocate. Many felt they would shame their families if they stayed or, in some cases, faced danger (e.g., being burned alive). They ultimately settled in Ahmedabad to live a life of daily begging since employment is nearly impossible for them.

A picture I took of the community.

These are the small carts they sit in to beg. They are pushed in these carts because their feet are too deformed to walk.

With the help of organizations like the Gandhi Leprosy Seva Sangh and Manav Sadhna, and thanks to people like Chris who devotes his time to serving others, Ahmedabad became a refuge for these people who had been outcast by society. Over time, medication has nearly wiped out leprosy from the entire community. Today, 2nd and 3rd generation children of lepers have no indications of leprosy and are 100% free of the disease. A variety of programs are also implemented in the community, including toilet installations, tree plantations, preschools, yoga classes, and a huge community center that includes a kitchen, auditorium, and fitness center.

Krishna (as Chris is now called) with a group of students he has been teaching.

In spite of their progress, the Loving Community and all its members still face the issues of stigma and similar poverty challenges found in slum environments.

Every year during the monsoon months, for example, the entire community is swallowed up by flooding, due to poor architecture and drainage systems.

Still, they continue to live in the moment.

One day during these heavy monsoons, while an international volunteer was outside in the rain taking measurements of some of these homes and was wading knee-deep through the water, he approached an elderly man standing outside his home. The man’s home was completely flooded with water everywhere.

As both men stood in the rain, the heavy downpour continued. The volunteer yelled some questions to the old man about the size of his home and the dimensions of the room inside.

The old man, also standing knee deep in water, replied instinctively, “Aren’t you going to come inside first so I can offer you some tea?”

The volunteer was speechless.

This is what living in the present is all about. Never mind the torrential rains. Never mind the flooding of the community. Never mind the destruction of my house. I have a guest in front of me. I must offer him tea. And I must do so now. The great, eternal, indestructible ‘now.’

This unbreakable attitude by a man who had no possessions, who was an outcaste and an untouchable, whose house had just flooded – yet who still retained the same compassion to a stranger as though he were rich and extended the same hospitality as though it were sunny – is a reminder that moments are what we make of them.

C.S. Lewis said that “the Present is the point at which time touches eternity.” Which is to say, do not give the future your heart, and do not promise your heart to the past. Living is in the present and the present alone can make us eternally happy. We won’t find God in some imaginary future. Instead, we find him in the here and now: in the middle of a monsoon, in the face of an international volunteer offering his assistance, we find him in a hot cup of chai amidst a flooding home, and in the humility and humanity of an untouchable leper.

This past February, two of my fellow volunteers were architects from Norway. Learning of the annual monsoon floods in the Loving Community, they came to Ahmedabad in order to design a blueprint for a makeover to the community. The goal was to avoid future flooding. They showed us the blueprint for feedback and we offered minor thoughts.

But as they were reviewing the blueprint with the community elders, the conversation went something like this:

Norwegian architects: “We have put together a design for your community that should help prevent flooding during the monsoons.”

Community elders: “Monsoon time? That’s not for another 4 months! Why are we talking about it this now? Let’s have some chai.”

Chai time is the one thing in India that seems to run like clockwork, even at times when it shouldn’t.

This clock hung in several homes here. Reading the time is much harder than reading the message, but maybe that was the point