Lesson 2: MacGyver was Indian.

Many of you will recognize this guy.

His name was MacGyver, a secret agent by day and a wizard by night. An all-around boss.

In every episode, MacGyver would always find a creative way to get out of a life-or-death situation using the most basic items around him. He would diffuse a bomb using only a paper clip. He could plug sulfuric acid leaks with chocolate. He once built a defibrillator to resuscitate his dying friend using only candles, a microphone, and a doormat.

And my time here in India has now convinced me, more than ever, that MacGyver was Indian.

Don’t believe me? Look around.

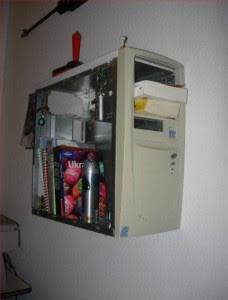

Shower heads made out of steel pots.

Water pumps powered by motorcycles.

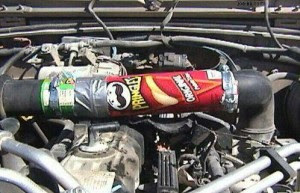

Car engines running on Pringle cans.

Welcome to India, an adult Legoland where automotive repair is just a potato chip away. Where if life gives us lemons, we freaking make watermelon juice!

There is a name in India given to this ingenuity/lazy, creative fixes to problems. It’s called jugaad (pronounced jugaar). It’s the art of solving a problem using only the items you have at your disposal. Sufficiency not necessity. Improvising not planning. The result is a patchwork-like invention that could literally be duct-taped together with a piece of gum. It won’t look pretty, but it will solve the immediate problem at hand.

Sometimes functioning means more than finishing.

Jugaad is everywhere I go in India and everywhere I look.

To me, this was just a plastic water bottle. When the water was done, the bottle was done.

But to a group of children in Goa, it was the cricket wickets on the beach.

To a tattoo artist in Baga, it was an advertisement to let motorists know that he also sells diesel.

To a home owner in Mumbai, it was the difference between cold water and hot water.

To college students, it was the life of the party.

To laborers, it was a time saver.

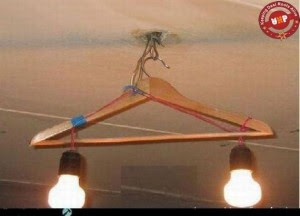

And for a newlywed couple in a small town, they were not water bottles, but a beautiful outdoor chandelier.

In India, one man’s ceiling is another man’s floor.

If you’ve never heard of jugaad, read about it. It’s the art of innovative frugality. Many business scholars and startups have studied it, published it, replicated it, and sought inspiration from it. In India, it’s virtually a philosophical outlook necessary to keep the country’s wheels moving. Its existence can be a curse and a blessing for those living here.

For one thing, it means no excuses. No water? No matter! Jugaad the problem!

Electricity went out? No stress! Just heat the toaster!

Laptop dying? Time to bust out those AA batteries!

No Ipod while cooking? Laptop-in-lunghi time!

Jugaad is the economic model that would put Home Depot out of business. A framework where every item is a tool and if it’s not, then you bloody turn it into one.

In the jungle that can be India, jugaad is a survival skill. No time for perfectionists here. It’s about making do and moving on. Finding options in nothing and going with something. Yes, technology is wonderful to have but if you don’t have it, you just replicate it, silly!

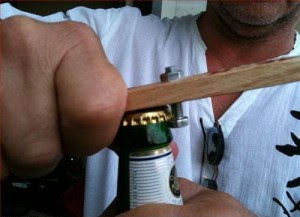

Jugaad throws all rules out the window. There is no instruction book, no parts, no warranty. Your creativity is your hammer, and your ego your nails. Yes, you will get hurt. But if your ‘wooden basket’-powered satellite dish works and you get the cricket match on, then that’s the only score that matters.

But it’s not just about building things. It’s about solving things. Not with what you need, but with what you’ve got.

Newton discovered gravity, you say? Please! While the apples were still falling on top of his head, Indians were using their heads to defy gravity.

Air conditioners were built in China? Maybe. But dual air-condition zones began here.

People often ask why there are no refrigerators in India. The answer is because we used the Chinese air conditioner to cool our beers. Simplicity overlooked.

Indians aren’t frightened by the new ideas, they’re frightened by the old ones. That’s why a human head is used as a crane, why a pair of pants is an energy efficient air conditioning system, and why an actual air conditioner is also a refrigerator. It explains why everything here has more than one purpose and why even an empty beer box transforms into a planter for a fake tree inside of a restaurant.

And why the hooks on the back of a rickshaw transform into a backpack holder to transport 9 children back home from school.

This is India’s version of the “chicken or the egg.” Jugaad works because Indians are packrats. Indians are packrats because they jugaad.

To see this first-hand, go into the home of any Indian. Open their pantry. You will see peanut butter jars from 1984 with lentils inside of them. Go in their cupboards. Every old t-shirt is now a rag to wash the car. Ever watch an elderly Indian person unwrap a gift? It’s like watching a movie in slow motion, it’s the most anti-climactic thing you’ll ever see in your life. A regift waiting to happen.

For all you non-Indians, now you understand why we can be so cheap.

But the truth is, Indians are the world’s best recyclers. We find use in everything. We were taught this as kids.

Girl: “Papa, my bookshelf broke! Can you buy me a new one?”

Dad: “I will get you a better one, don’t worry.”

Boy: “Papa, papa, my belt broke! Can you buy me a new one?”

Dad: “Beta, you are getting too fat. But don’t worry, I will get you a new belt.”

Boy: “But Papa! I will be stabbed to death like this!”

Dad: “No, no beta. You are looking too sharp, tooo sharp!”

Our parents taught us that everything has some value.

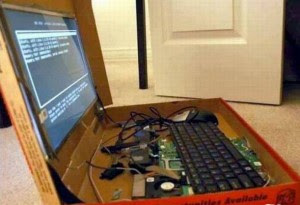

Dad: “What are you doing?”

Girl: “Throwing away the pizza box.”

Dad: “Why would you do that?”

Girl: “Umm, because it’s empty? We finished the pizza.”

Dad: “Beta, this is not just a pizza box!”

Of course Indians are good with computers! We have pizza boxes as laptop cases!

The spirit of jugaad also helps explain how people in India will find some way – any way – to make a living.

A bike and a pot?

A chai wala on wheels!

A scale?

A street-side weighing station!

A rope, two trees, and a pole?

A trapeze, high-wire act put on by street kids.

A coconut shell, bamboo, and horsehair?

A traveling musician.

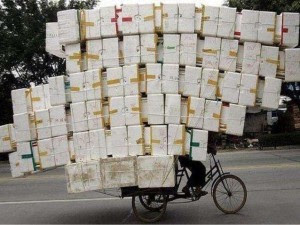

And if you are in the business of transporting items from place to place, a single bicycle can move mountains.

Yes, we’re good at physics too.

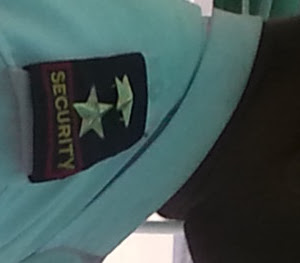

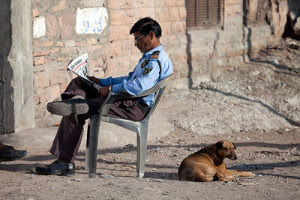

But the profession that has captivated my attention here, more so than any other, are security guards (or watchmen as they are called). To me, these guys are the jugaad of all trades. They are versatile in nearly every part of the business where they are employed. I mean every part.

At one hotel I stayed, every security guard was armed only with a slingshot. I didn’t know what to make of this. But it all made sense the next morning when I caught this security guard using his slingshot to shoot at a bunch of birds sitting in the tree. (If he doesn’t guard the trees, the birds will make a mess below. And going number 2 on top of the head of a guest means no more business). So slingshots it is!

At another hotel I was at, the security guards doubled-up as tour guides for the evening boat rides around the lake. They were well-versed in the history of the town, when each structure was built, which fish were popular in the lake, and the best places to buy saris and spices. They answered any questions you had and could even accompany you on an all-day tour if we planned ahead.

Outside of another store I was at, the security guard was also in charge of marketing and advertising. I watched as he left his post. I followed him down a few streets as he distributed flyers at a local gathering. He was trying to attract more customers for the store.

Security guards here are the bellboys, porters, parking attendants, doormen, bird watchers, repairmen, tour guides, marketing directors, and deliverymen all rolled into one. They fulfill every business need as it arises. Except, of course, maybe securing the premises.

In India, every item, every person, every part, every soul will find some purpose here. You just have to be creative, open minded, and flexible when it comes to understanding what “value” really means. Things are not limited to just one function, just as ideas and thoughts are not limited to just one interpretation. It is the Long Arm of Plurality at work once again.

Of course, jugaad is a double-edged sword. Despite its entrepreneurship, it leads to complacency and laziness. It can be unsafe and unsustainable and often times leads to more problems than answers. Ask anyone who lives here.

But for many here who are impoverished, it can be the shortcut around governmental/bureaucratic red-tape or the cheap fix to a hungry and starving population. As a lifeboat, it accounts for miracles.

I saw one such miracle inside of a slum I was working at in Ahmedabad.

What is this?

The answer should be that it is nothing more than a photograph of a very tiny second-floor bedroom in the middle of a slum in Shahpur.

But that’s not the answer, because this tiny second-floor bedroom has been transformed into a classroom for 40 young children inside the slum.

The children meet here everyday because there is no after-school program for them when they are done with government school. Their parents cannot afford to send them to private tuition. The slum had no space for a school. So when an elderly woman inside the slum, who lived her years inside of this bedroom, heard about this, she voluntarily decided to give up her only asset so that the children could use it as a classroom to learn.

And just as a fake tree grows from an empty beer box, a small bedroom gave birth to a street school.

Today, the children of this street school use jugaad on a daily basis. They have to.

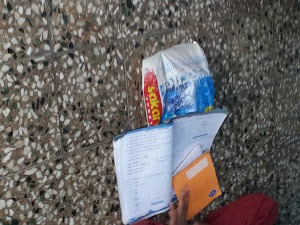

This isn’t just a plastic bag.

It is the backpack that 12-year-old Vishal uses to carry his books, his papers, his homework, and his pencils everyday. The ground is his desk.

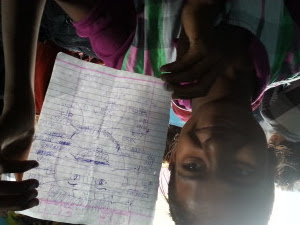

And this isn’t just a piece of paper with a face on it.

It was our two-hour lesson of how to identify parts of the human body in Hindi and English because we had no books.

The resources available to us were terrible to say the least. One day there was chalk, the next day there was not. Electricity came and went. There were no seats to sit on or tables to write on. Some kids had pencils, some did not. But in the spirit of jugaad, we made do with what we had. Rather than wasting our time coming up with excuses, we kept on teaching. And rather than complaining that they weren’t comfortable, the students kept on learning.

But jugaad can only go so far in India. At some point, its magic fades and there is a need for real resources, and real tools, and qualified, skilled people who know what they are doing. Especially inside of the classrooms. These kids need good books, and good teachers, and good spaces to learn. These kids all deserve a chance.

I remember one day when a boy in the street school was so eager to prove to me he could read English, he opened up his schoolbook and showed me the words he had copied down in class. The words were written in his own handwriting, and he pointed at each word in English and correctly pronounced it for me.

“Hill.”

“Tree.”

“River.”

“Very good,” I said. I closed his book and re-wrote the word “hill” on another piece of paper.

“Now read this word,” I said.

He sat in silence. He had no idea how to read the word, because he had no idea how to read at all. He had only learned to memorize the sounds of the words he had copied down and then memorized the words based on their positions in his book.

“What’s a hill?” I asked him.

Again, silence. He had no idea. He was only taught to copy down words, but he had no idea what they meant. I explained each word to him and drew a picture. I asked him to continue reading for me the words he wrote down.

“House.”

“Sun.”

“Lake.”

“Say that word again,” I asked. I pointed at the word in his book.

“Lake,” he repeated.

(The word in his book was spelled “lack.”)

“Say it again,” I asked him.

“Lake.”

“Who taught you that spelling?” I asked.

“My teacher,” he replied. He attended a government school where hundreds of street kids go. There is one teacher for 50 students. Sometimes the teacher comes on time, sometimes not at all. The teachers are hardly educated and some have not even completed school. They teach what they know. But many times they teach what they don’t know and that is the scary part.

Even more dangerous is that the students here learn through rote memorization. If the teacher is wrong, the student has memorized it the wrong way 1,000 times. It took me a lot of convincing to teach him that it was spelled “lake.” He finally relented. He promised me he would correct his teacher the next day. (I could only imagine how that conversation would turn out.)

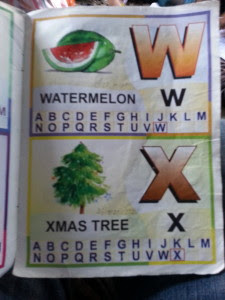

It’s not just the teachers, though. The resources aren’t much to sing about either. One girl showed me her English book. Check out the word for “x”.

I recently read an article in the paper here that in some Gujarati textbooks, students are being taught that “Japan dropped a nuclear bomb on the U.S. during World War 2.” And Gandhi, the books teach, was killed on October 30, 1948 (Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869 and killed on Jan 30, 1948). Combine these poor resources with rote memorization and the result is massive ignorance on the part of a young population. Forget world history, they don’t even know their own.

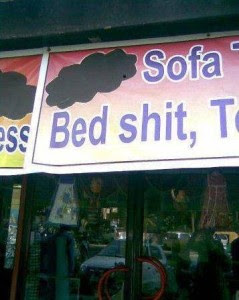

Over time, it is this ignorance and illiteracy that leads to the notoriously hilarious Indian street signs that we are all guilty at laughing at in Buzzfeed articles or email chains.

Nothing like foot ready to go.

No soft drinks here.

The list of these signs goes on and on.

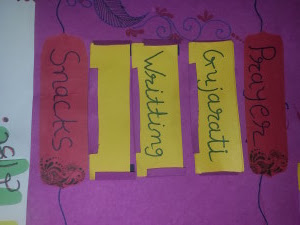

As I was inside of a classroom one day in Ahmedabad, realization set in when I saw this wall.

What is most tragic is that the word “writting” was written by the teacher, not a student. Suddenly, the street signs I was laughing at above made more sense to me.

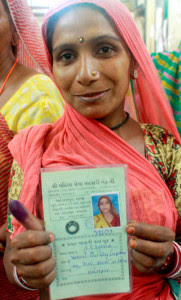

Illiteracy is so rampant here that the government has to mint currency with it in mind.

Take this coin worth 2 rupees, for instance.

The number “2″ is not enough to communicate the coin’s worth to the almost 300 million illiterate people in India. So, instead it includes a picture of a hand with two fingers raised. Like a child’s storybook, pictures must do the talking.

Because many here don’t know to write or sign their own names, signatures are replaced with thumbprints.

Her signature is the ink on her thumb.

As difficult as it is to see these children learn in these environments, it is more hopeful than hurtful. And that’s because despite what jugaad can’t fix permanently, it is the spirit of it that counts day in and day out. It is a form of human alchemy that everyone seems to be blessed with. It reminds Indians here, especially the poor, that to those who are willing, everything is possible.

One morning, on a day when school was closed, I saw these two boys from the slum sitting down in a corner of the community center. It was jugaad at work. One math book (pages were missing) between two children (different grade levels), with no excuses not to succeed. Here, people never wave the white flag. They just find another way.

Slum life in India can be tough, unrelenting, and downright hard. But to those who live in it, they wear jugaad on their chests and march on proudly.

MacGyver would be proud.