I have spent the past few months traveling in India and volunteering with an NGO. Hundreds of stories later, I am trying to find the right words to narrate my time here.

India cannot be boiled down to a list. No country can. But whether in the five-star hotels of Kerala or in the crowded slums of Ahmedabad, I offer 5 lessons from India that applied virtually everywhere I went.

The expression “packed like sardines” never met India.

And that’s because the concept of space is crucial to understanding India. Not only is there more space than you think, but in India there’s more to space than you think.

If you have never been to India, it is unlike any other country in the world. Rather than one nation, it is more like a thousand different nations held together by a very thin, dangling thread. How it functions day to day is a mystery not just to strangers. The locals describe it as bharosa, a type of trust, faith, belief and confidence that things will just work out in the end.

It is this same bharosa that governs the streets of India everyday. It alone explains how goats, rickshaws, cows, buses, cars, people, and wagons can all occupy the same given space in the very same moment. Here, room is made for everything and everyone.

One day this past February, while I was traveling through Mumbai, I came across this random motorbike ahead in the road. For no special reason, I took a picture.

How many people do you see on the motorbike?

Two, right?

It’s not a very inspiring photo. Nor a very telling one. It’s simply an ordinary photograph of two people – a man and woman – seated on a motorbike, with some shopping bags squeezed on the side between them.

In fact, if the motorcycle drove off ahead of us, it would have been a photograph I would have forgotten I took.

But as the motorcycle slowed down a few seconds later, and we passed it, I looked again.

Now how many people do you see on the motorbike?

Did I miss the part when the two kids materialized out of nowhere and hopped on in front of each parent?

No. It’s just India constantly messing with my perspective. And constantly reminding me that people here don’t waste any amount of space, ever! Where two can fit, four can manage.

Just look around and you will see it in practice everywhere.

Like an un-squeezed fruit, Indians can make juice out of any space.

Do you remember this game as a kid?

India is an endless game of Twister. Especially inside the trains.

While aboard an Indian train, you must be prepared at all times for your next spin of the Twister wheel.

Let me explain this human Tetris. You could be seated on top of someone”s leg, have an armpit in your face, with a child’s foot in your nose, and indefinitely someone will approach you while walking on top of the backs of sleeping people on the floor. Despite seeing your obvious discomfort, he will look at you with a sheepish grin on his face and start wobbling his head at you. The head wobble can mean anything in India. Here it means: “I see you have no more room, and I don”t have a train ticket, but will you scoot over for me anyways?”

You cannot breathe (because someone else has just stepped on your head), so you don’t respond to him.

He smiles at you again. Another wobble of his head. “Sir, kindly adjust.”

It is a request, half-threat, and pleasantry all in one. It means, “Sir, don’t be alarmed. I am coming. We will manage this.” Before you can even look at him, he is on your lap, removing the foot from your nose and putting it in your ear. As he squeezes in next to you with his family of three, Ajay (who has now introduced himself and his family to you) smiles and asks you if you are married. You think of finally opening your mouth and saying something. Too late. Your voice is drowned out by the chai wala passing through the compartment.

“Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.Chai.”

You watch as Ajay immediately signals to the chai wala using only his eyebrows. It is an impressive nonverbal skill to say the least, and Ajay has obviously mastered it. More impressive is that the chai wala (with x-ray vision) spots Ajay’s eyebrow movement buried in the darkness beneath the two other guests who have piled on top of him.

The chai wala stops and looks directly at Ajay. “Chai?”

Ajay simply closes both his eyes at the same time while slightly tilting his head to the left. Contract signed.

As you sit there, stunned, you now understand why yoga began here. You have to be this flexible in both mind and body to survive.

It was everywhere I looked, everywhere I turned, everywhere I escaped to. Just when I thought our rickshaw was at full capacity, four more Indians piled aboard, reminding me that an inch of space is like a dental cavity in India. Like a national toothbrush, we must each do our part to fill it and keep the Indian dentist gods happy.

This is an empty, normal sized auto rickshaw.

This is Twister-nation.

Like Twitter characters, space in India is never wasted. It is used wisely and creatively to fulfill some purpose.

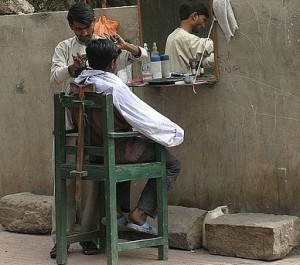

While traveling to one of the slums in Jamalpur, Ahmedabad, I approached an underpass. In the U.S., these are generally empty spaces under a freeway.

Not here.

That’s right, buddy! A combined barbershop and fresh vegetable market! Because there’s nothing better than buying cabbage while getting a haircut.

Don’t be deceived though. Here in India, sometimes the more daunting the space, the better the destination. Like life, you just have to stick with it.

What do you see here?

Nothing here but garbage and filth. Time to turn around?

Not so fast. The wise remind us to “Sow the seeds and trust.”

So trusted we did and onward we marched, keeping our feelings to ourselves. A few turns later, the very same space opened up to this paradise.

Turned out it was the only way to get there.

This pollution vs. purity contradiction was everywhere in India. Even places it shouldn’t have been. Like Haji Ali, a Mumbai landmark.

But to reach this historical and legendary and mystical wonder, you walk through this causeway, nearly a kilometer long.

Pardon my Western eyes. But there’s generally a separate space for landfills and a separate space for landmarks, no?

Not here. In India, pollution and purity aren’t just neighbors. They’re freaking roommates.

The same holds true for rich and poor. This is the 5-star Taj Hotel in Mumbai.

And these are the faces that await you as you step outside the Taj.

As the saying goes, “A poor man begs outside the temple, a rich man begs inside.”

While part of me is disturbed and embarrassed by such spaces in India, a part of me is also in absolute awe.

Because whether it’s the trains, or the rickshaws, or the streets, or the slums, whether it’s the underpasses or the alley-ways or the areas just outside the 5-star hotels, spaces in India do not discriminate. They are the great, blind equalizers of Indian life. A place where the pluralities of India – rich, dark, poor, tall, and everything in between – melt together without choice.

I will never forget this train station in Gujarat.

As we were waiting to board our train one early morning, I watched the locals coming in. Some were Hindus, some Muslims, some Christians. Some were old, some were young, some were rich and some were poor. Still, fatigue plagued them all. One by one, they plopped on the platform and fell asleep waiting for their trains to arrive. And in this shared slumber, in this shared space, I watched as two complete strangers shared the same blanket.

Like the railroad platform, spaces in India can be transformative. They house contradiction and promote unfamiliarity. I like the idea of this plurality. It can be unusually healthy.

This is why outside a restaurant in Goa, I saw two paan-walas competing for customers in the very same space side-by-side.

Talk about bad business. The lawyer in me wonders casino online if they forgot to include an exclusivity clause? No. This is probably an M&A waiting to happen.

But I saw this pluralism everywhere. In the strangest of spaces, during the strangest of moments.

I saw it on Jew Street, in Kochin, where Jewish merchants decorated their stores with Hindu swastikas.

I saw it in Kumarakom, where our Hindu driver Babu displayed a Christian cross on his rearview mirror.

I saw it in Alleppey, where a local Ayurvedic doctor in a remote fishing village decorated his small wall with pictures of Krishna, Christ, Mecca and Mahavir.

I saw it across the street from the Gandhi ashram, where a small roadside shrine catered to rich men and stray dogs alike.

I saw it near Shahpur, where rich and poor alike paid tribute to a statue of the Buddha. It mattered little that the statue was beheaded. In this space, emotion trumped reality.

I saw it in Mumbai, where a grandson and his grandfather both prayed to Hanuman, the mythological flying monkey god of India. In that small space, an unspoken affirmation is passed down from old to young: no matter what your age, you are never too old to believe in flying monkeys.

And I saw it in Ram Rahim Tekro, a large slum in Ahmedabad where I worked, where a Hindu priest read the Bhagavad Gita in front of a Muslim mosque.

He then played with a young Muslim child in his arms.

An interesting aside about Ram Rahim Tekro. Though a slum, it is the only place in Gujarat that remained at peace after religious riots in 1969, 1985, 1992, and 2002. This is shocking when you consider its recipe for disaster: (1) it is one of the rare slums that is home to 60,000 Hindus, Muslims, and Christians; (2) the population is highly uneducated; and (3) highly impoverished.

Poor people no education historically religious rivals = unprecedented peace. (Go figure, all you social scientists.)

The secret to the math is that Ram Rahim Tekro is truly a magical place. The slum prides itself on diversity. It is one of the rare places on Earth that has a Muslim dargah (tomb) standing just feet away from a Hindu temple. In its history, neither has ever been vandalized.

During a day-long medical screening camp that we did there, I soaked in this Hindu-Muslim-Christian dynamic. It was bewildering. As I was checking in people with health-related problems, I took down their names.

Ali Kapadia. Rafiq Parmar. Jyoti Sheikh. If they were Muslim or Hindu, I could not tell and, frankly, it was insulting to them for me even to wonder. It did not matter here.

What mattered here was raw kindness. From the heart. You know, the real sincere kind. Muslims here celebrate the Hindu festival of Diwali with such fanfare, they would shame most Hindus. And Hindus celebrate Eid like one of their own. For added measure, a Muslim and Hindu child each recited the Lord’s Prayer for me. Small children are left behind in the custody of neighbors belonging to any religion while their parents are running errands. Raised in this space, naturally the children become global citizens overnight.

But most of us will never learn from these children because they are disregarded as slum-dwelling ratpickers. (That is for another post.)

One man

revealed to me the real secret to the slum’s diversity. A story shrouded in historical legend of a deep friendship between two 15th century friends, one Muslim and the other Hindu, Shah Alam and Narsinh Bhagat. True or not true, he believed it, and that is all that really matters.

No matter where you are traveling in India, you will need to adjust. Adjust your seat, adjust your attitude, adjust your belt (you will eat here), and adjust your senses to the overload that is everything Indian.

And the key isn’t simply to adjust, but to “kindly adjust.”Because adjusting isn’t enough if you’re not doing it with a smile and a head wobble. (The Indian need for adverbs is well-documented. As Russell Peters observed, his father would tell him as a child when he needed to go pee, “Ok Russell, go to bathroom, but go nicely!”).

When you kindly adjust in India, you will make space for one more friend, one more lesson, one more experience, and one more cup of chai with your new train buddy Ajay.

After all, this is India. There”s always space for more.